Rituximab offers an alternative to current immunosuppressive therapies for difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome. The best outcomes are seen in patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome who have failed to respond to multiple therapies. By contrast, the benefits of rituximab therapy are limited in patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, particularly those with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Therapy with plasma exchange and one or two doses of rituximab has shown success in patients with recurrent FSGS. Young patients and those with normal serum albumin at recurrence of nephrotic syndrome are most likely to respond to rituximab therapy. A substantial proportion of rituximab-treated patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy show complete or partial remission of proteinuria, and reduced levels of phospholipase A2 receptor autoantibodies, which are implicated in the pathogenesis of this disorder. Successful rituximab therapy induces prolonged remission and enables discontinuation of other medications without substantially increasing the risk of infections and other serious adverse events. However, the available evidence of efficacy of rituximab therapy is derived chiefly from small case series and requires confirmation in prospective, randomized, controlled studies that define the indications for use and predictors of response to this therapy.

Rituximab is a chimaeric monoclonal antibody against CD20, an antigen expressed during most stages of B-cell development. Binding of rituximab to CD20 causes rapid depletion of B-cell populations and has been used for the treatment of a number of autoimmune disorders. 1 This agent is approved for therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, vasculitis and rheumatoid arthritis. 2,3 In addition, rituximab has been tested in clinical trials for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus, and is used off-label for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. 2 Rituximab has also been used in the treatment of patients with nephrotic syndrome, including those with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome or steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and membranous nephropathy (Box 1). 4,5,6,7

This Review provides an overview of the available data on the safety and efficacy of rituximab in the treatment of paediatric and adult patients with nephrotic syndrome. Most reports are anecdotal or limited to case series, as limited data on the efficacy and safety of this treatment are available from prospective controlled trials. Owing to the retrospective nature of these reports, the indications for rituximab administration to patients are unclear and definitions of response are heterogeneous. Accordingly, we have reviewed studies on the efficacy of rituximab in patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, recurrent FSGS or membranous nephropathy, in which achievement of complete or partial remission is reported on the basis of standard definitions, or by the authors of individual studies. 8,9,10 For patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome, we have reviewed studies in which the frequency of relapses, the use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents and the need for re-treatment with rituximab was reported.

Nephrotic range proteinuria

Adults: Proteinuria >3.5 g per day.

Children: >40 mg/m 2 per hour; urinary protein:creatinine ratio >2 mg/mg or >200 mg/mmol.

Steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome

Two consecutive relapses while receiving predniso(lo)ne on alternate days, or within 15 days of its discontinuation.

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

Lack of remission despite 4–8 weeks of therapy with daily predniso(lo)ne at a dose of 60 mg/m 2 or 2 mg/kg (maximum 60–80 mg) per day.

CNI-dependent nephrotic syndrome

Remission of steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome is achieved during therapy with CNIs (tacrolimus or ciclosporin).

CNI-resistant and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

No response to therapy with predniso(lo)ne as defined above, or to CNI therapy for 3–6 months.

Complete remission

Adults: Proteinuria 30 g/l), and stable renal function.

Partial remission

Adults: Proteinuria 0.3–3.5 g per day and/or ≥50% decrease in proteinuria from baseline, and stable renal function.

Children: Urinary protein:creatinine ratio 0.2–2.0 mg/mg or 30–350 mg/mmol; and serum albumin >30 g/l.

Abbreviation: CNI, calcineurin inhibitor.

CD20 is a calcium-channel protein expressed in B cells during maturation, in precursor B cells and mature B cells, but not in plasma cells. 11 Although the function of CD20 is not clear, binding of rituximab or other anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies to this ligand in vitro activates apoptosis via complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, which leads to rapid depletion of B cells. 11,12 After binding to rituximab, CD20 is translocated into lipid rafts, where signalling through tyrosine kinases, mitogen-activated protein kinases and phospholipase Cγ mediates inhibition of B-cell growth or leads to apoptosis. 12,13,14

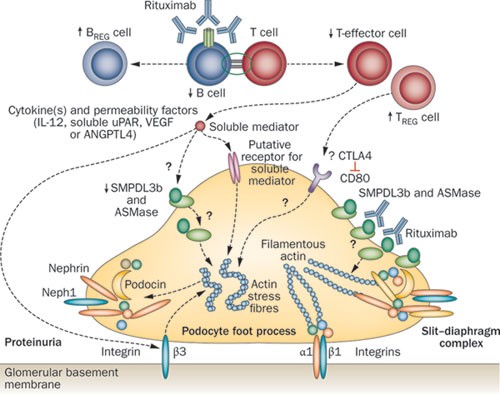

The mechanisms by which rituximab induces remission in patients with nephrotic syndrome are unclear (Figure 1). Proteinuria in patients with minimal change disease and FSGS might be mediated by unrecognized permeability factor(s), perhaps a T-cell cytokine. 15 Since B cells activate T-helper cells through antigen presentation, depletion of B cells might alter T-cell function or subpopulation expansion. 16 Alternatively, the beneficial effects of rituximab therapy in patients with nephrotic syndrome might be mediated through restoration of T-regulatory (TREG) cell populations and/or upregulation of their functions, similar to changes seen in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus and cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis. 17,18,19,20,21,22 Another study showed that the proportion of B-regulatory (BREG) cells was increased during B-cell recovery in mice with autoimmune diabetes when they were given rituximab. Rituximab therapy may therefore induce TREG and BREG cell populations that restore immune tolerance. 23

Several authors suggest that patients with nephrotic syndrome have deficient TREG cell function. 24,25,26,27,28 In the 'two-hit' hypothesis of minimal change disease, proteinuria is initiated by podocyte expression of CD80, a T-cell co-stimulatory molecule. 29 Persistent proteinuria might result from faulty cessation of CD80 expression, owing to impaired podocyte autoregulation or impaired production of soluble CTLA4 by circulating TREG cells. After rituximab treatment, patients with membranous nephropathy have transiently increased numbers of CD3 + and CD4 + T cells, and a persistently increased number of natural killer cells, but no change in the number of TREG cells. 30 However, two reports, currently published as abstracts, indicate that therapy with rituximab produces an absolute or relative increase in the number of TREG cells. 31,32

The rapidity with which rituximab reduces proteinuria in patients with idiopathic or recurrent FSGS suggests that this treatment has direct actions on the podocyte (Figure 1). The CD20-binding region of rituximab crossreacts with an amino acid sequence within acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b (SMPDL3b). 33 CD20 engagement by rituximab upregulates sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase (also known as acid sphingomyelinase) activity in B cells. 34 The number of SMPDL3b + podocytes was lower in patients who developed recurrent FSGS after renal transplantation than in those who did not. 35 Normal human podocytes incubated with sera from patients with recurrent FSGS showed downregulation of SMPDL3b, the presence of actin stress fibres and disruption of the cytoskeleton. These findings were attenuated or reversed in the presence of rituximab. 35 Interestingly, in a podocyte model of HIV nephropathy, an altered actin cytoskeleton and diminished podocyte attachment were associated with decreased sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase activity. 36 However, the role of this enzyme in the pathogenesis of FSGS requires confirmation in further studies.

Finally, patients with recurrent FSGS have high levels of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor (uPAR) in serum. 37 Experiments using transgenic mice and podocyte cultures show that sera from such patients activates podocyte uPAR and integrin-linked protein kinase, leading to foot process effacement, proteinuria and FSGS. Moreover, elevated serum levels of soluble uPAR are associated with a decrease in the number of TREG cells. 38 The effect of rituximab on serum levels of soluble uPAR and activation of podocyte β3 integrin is being examined in patients with FSGS. 39 These findings need confirmation in large studies and across different populations.

CD20 is internalized after binding to rituximab. Consequently, CD19 (another B-cell surface antigen) is used as a marker for reliable monitoring of B-cell numbers in rituximab-treated patients. 40 Pharmacokinetic studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis show that rituximab follows a two-compartment model with a terminal half-life of 19–22 days. 41,42 The terminal half-life of rituximab is 2.7-fold longer after the fourth dose than after the first dose. 43 Patients given four doses of rituximab also have a twofold higher serum level and prolonged serum half-life of the medication compared with patients who received a single dose. 44,45,46

The timing of re-treatment with rituximab is based on either the extent of B-cell recovery or the occurrence of one or more relapses. In one study, doses of rituximab were repeated in 12 of 19 patients who showed recovery of B cells after the initial clinical response. 48 Others have used multiple courses of rituximab to achieve sustained B-cell depletion for 15–18 months in patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. 49,51 Prolonged B-cell depletion was associated with sustained remission for 2 years in two-thirds of patients, despite B-cell recovery, and without the use of additional immunosuppressive agents. 51 Other research groups have successfully used re-treatment with rituximab to treat relapses. 44,52,53

It is speculated that proteinuria in the nephrotic range might attenuate the biological effects of rituximab by causing increased urinary loss of the drug. 48 Serum levels of rituximab were lower in patients with membranous nephropathy with substantial proteinuria than in those given rituximab during remission, or in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. 30,45 Decreased efficacy of rituximab in patients with proteinuria in the nephrotic range has been proposed in other studies, 48,53 which suggests that rituximab should be administered during remission. Although reduction of proteinuria by maximal inhibition of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis might potentially reduce urinary losses of rituximab and increase its efficacy, this strategy requires prospective confirmation.

Most studies of patients with nephrotic syndrome have used a rituximab dose of 375 mg/m 2 once a week for 1–4 weeks, which is adapted from the standard regimen for lymphoma. Serum levels of rituximab are similar irrespective of whether it is administered to children or adults, and whether doses of 375 mg/m 2 or 1 g/m 2 are used. 45 Evidence from case series suggests that remission is prolonged after therapy with 2–4 doses of rituximab; 52,54,55 therefore, we propose that patients with nephrotic syndrome should receive two or more doses of this agent. Prospective studies are, however, required to examine the relationship between the number of rituximab doses and the chronology of B-cell recovery, and how this relationship affects the clinical response.

Approximately 40–60% of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome have frequent relapses or are dependent on steroid treatment. 56 Although medications such as cyclophosphamide, levamisole and mycophenolate mofetil reduce the frequency of relapses in most patients, 57,58 the clinical management of some patients is difficult. Treatment with calcineurin inhibitors is effective, but is associated with considerable toxic effects such as nephrotoxicity, hyperglycaemia, headaches and dyslipidaemia. 57,58,59 Therapies that enable steroid sparing without substantially increased adverse effects are, therefore, needed.

Rituximab was first reported to induce remission of nephrotic syndrome in a boy aged 16 years who was treated for co-existing idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. 60 Since then, other studies have shown the efficacy of this agent in patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (Table 1). 44,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,61,62,63 Patients in these studies received rituximab as 'rescue therapy', several years after the onset of disease; previous therapies included three or more immunosuppressive agents in 30–100% of patients and calcineurin inhibitors in 42–100% of patients.

Almost 60–70% of patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome treated with calcineurin inhibitors achieve complete or partial remission, 9 and at present no alternative agent shows superior efficacy. However, therapy with rituximab might be useful in two instances. First, in patients who respond to calcineurin inhibitors, treatment with 2–4 doses of rituximab might be used to maintain remission and enable withdrawal of calcineurin inhibitors, especially in the presence of drug-related toxic effects. Second, the results of retrospective case series suggest that treatment with rituximab might be effective in some patients with nephrotic syndrome resistant to corticosteroid and calcineurin inhibitor therapy. However, the results of a randomized controlled trial that examined the efficacy of rituximab in such patients were not encouraging. 66 Adequately powered studies with long-term follow-up of groups of patients stratified for renal histology are required to clarify the benefits of these treatment strategies.

Patients with idiopathic FSGS and persistent proteinuria in the nephrotic range are at risk of developing kidney failure that requires renal transplantation. Approximately 30% of such patients develop recurrence of FSGS after the first allograft. 80,81 Features associated with FSGS recurrence include onset of nephrotic syndrome below the age of 15 years, rapid progression to end-stage renal disease (within 3 years from onset), mesangial proliferation on renal histopathology, white ethnicity and nongenetic (immune) forms of FSGS. 82,83 The increased risk of FSGS recurrence in children who receive renal grafts from living donors 84 is balanced by the reduced risk of rejection and decreased need for immunosuppression. 85 Recurrence of FSGS usually occurs within hours to days after the transplant procedure, and is characterized by proteinuria in the nephrotic range and progressive hypoalbuminaemia. 6 These patients are at increased risk of allograft failure (5-year kidney graft survival is 57% in patients with recurrent FSGS versus 82% in patients without recurrence). 86,87 After the loss of the first allograft, the risk of recurrence of FSGS in subsequent kidney transplants is 80–100%. 88

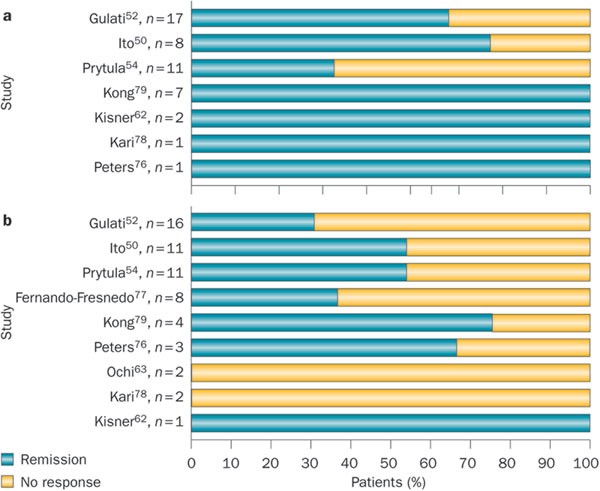

Strategies for the management of patients with recurrent FSGS include the use of plasma exchange or immunoadsorption in combination with high-dose ciclosporin and cyclophosphamide. By using these strategies, 70% of children and 63% of adults with recurrent FSGS achieve complete or partial remission. 89 In one case report, a decline in proteinuria was observed after rituximab therapy in a boy aged 12 years with recurrent FSGS treated for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. 90 Subsequently, some researchers have reported remission of proteinuria with the use of rituximab (2–6 doses of 375 mg/m 2 , administered once every 1–2 weeks) in conjunction with plasma exchange and post-transplantation immunosuppression.

Experience with rituximab therapy in patients with recurrent FSGS has been summarized in a systematic review 6 and a multicentre report (Table 4). 54 The review included data on 39 patients with recurrent FSGS. Proteinuria in the nephrotic range and hypoalbuminaemia were present in 74.3% of patients within 1 month of kidney transplantation. 6 Combined therapy with plasmapheresis and rituximab resulted in complete or partial remission of proteinuria in 64.1% of patients. The median time to best clinical response was 2 months (range 0.6–12.0 months). On univariate analysis, a young age at transplantation, normal serum albumin level at recurrence of FSGS and the need for fewer rituximab infusions was associated with an improved response to treatment. Response was not related to the kidney donor type (living or deceased), the use of pretransplant or post-transplant plasmapheresis, other immunosuppressive therapy or the post-transplant severity of proteinuria. On stepwise regression analysis, normal serum albumin level at recurrence (which implies mild FSGS) and young age predicted a favourable response to rituximab therapy. 6 The IPNA study showed that therapy with 1–4 doses of rituximab in combination with plasmapheresis resulted in complete or partial remission in nine of 15 (60%) patients (Table 4). 54 Five of the seven patients treated with B-cell depletion showed complete or partial remission; two patients (one with and one without B-cell depletion) were nonresponders. 54 In a review of data from 25 patients with recurrent FSGS treated with rituximab infusions and plasma exchange, the 12 patients who achieved remission had received rituximab infusions significantly earlier than the 13 patients who did not respond (mean 100.5 ± 95.4 days from the onset of recurrence versus 468.1 ± 379.8 days, respectively). 91

Table 4 Efficacy of rituximab in treatment and prevention* of recurrent FSGSIn another report, six of eight patients with recurrent FSGS refractory to plasmapheresis achieved complete or partial remission with 1–4 doses of rituximab. 92 Furthermore, patients who had relapses of proteinuria responded to re-treatment with rituximab. Treatment with plasmapheresis and two doses of rituximab induced complete or partial remission in four adults with recurrent FSGS (Table 4). 93 Other reports indicate similar findings that rituximab is effective in sustaining remission in patients who either do not respond to or who are dependent on plasmapheresis. 94,95,96 Although the possibility that these patients had a delayed response to plasmapheresis cannot be excluded, the timing of response correlated with that of rituximab therapy.

Combined therapy with rituximab and pretransplant plasmapheresis is useful in kidney transplant recipients at high risk of recurrence of FSGS. Therapy with 1–2 doses of rituximab and multiple sessions of plasmapheresis prevented recurrent FSGS in recipients of a second kidney transplant who were followed up for 12–54 months. 97 In a report, a girl aged 7.9 years with a history of recurrent FSGS was successfully managed using four sessions of plasmapheresis and a single dose of rituximab (375 mg/m 2 ) 21 days before transplantation. 98 In another report, administration of rituximab within 24 h after transplantation prevented recurrence of FSGS (Table 2). 35 Recurrent FSGS was noted in 25.9% of 27 patients treated with rituximab, compared with 64.3% of 14 patients who did not receive the medication. 35 However, the overall incidence of FSGS recurrence in this study was considerably higher than that reported in the literature; the recurrence rate in patients receiving rituximab was close to that cited elsewhere for untreated patients.

All patients with FSGS who are about to undergo renal transplantation should be advised about the possibility of recurrence of this disease. Pre-emptive plasma exchange should be planned in advance of living-donor transplantation. 99 Early and aggressive therapy with immunosuppression and plasma exchange should be initiated if proteinuria develops after transplantation.

The efficacy of rituximab in patients with recurrent FSGS is difficult to estimate owing to confounding effects from other concomitant therapies. Combination therapy with plasma exchange and rituximab has shown promise in the prevention and treatment of recurrent FSGS, but the efficacy of this approach needs to be examined in prospective controlled studies. 82 Rituximab is cleared from the body by plasma exchange; 100 we suggest, therefore, an interval of 36–48 h between rituximab infusion and plasmapheresis.

Membranous nephropathy is the principal cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults, 101,102 among whom idiopathic membranous nephropathy accounts for 32–80% of diagnoses. Secondary causes of membranous nephropathy include systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic infections (especially hepatitis B), medications or malignancy. 103,104 Spontaneous remission occurs in 30–40% of patients within 12–24 months. 105 Current therapies include inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, and combinations of corticosteroids with alkylating agents or calcineurin inhibitors. 106 The results of randomized trials indicate that therapy with the above-mentioned agents can induce remission in 59–90% of patients; however, relapse rates are high and patients with proteinuria in the nephrotic range can develop progressive renal failure. 107,108 The efficacy of rituximab was initially reported in eight patients with membranous nephropathy, 109 but this agent has since been used in the treatment of both idiopathic and secondary forms of the disease, as first-line therapy and after patients fail to respond to standard therapy.

Membranous glomerulonephritis is thought to result from an immune response in which podocyte antigens are targeted by circulating IgG4 antibodies. Subepithelial deposition of these immune complexes results in podocyte injury and loss of the filtration barrier. Of particular interest is an autoantibody against the M-type isoform of the phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R). 110 Support for a pathogenetic role of this autoantibody comes from findings of associations between titres of this antibody and nephrotic range proteinuria or post-transplant recurrence of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. 111,112,113 Positive staining for PLA2R was found in immune deposits in kidney biopsy samples from patients with membranous nephropathy. 114 Patients with membranous nephropathy and autoantibodies against PLA2R often also have elevated levels of antibodies against other antigens, including neutral endopeptidase, aldose reductase, superoxide dismutase 2 and α-enolase. 115 Although rituximab therapy does not remove circulating autoantibodies, treated patients show a decline in the titre of anti-PLA2R antibodies and remission of proteinuria. 45,111,114,116 Table 5 and Supplementary Figure 1 online show the clinical response of patients with membranous nephropathy to rituximab. 30,61,114,116,117,118,119,120,121 However, heterogeneity in previous therapies, dosing schedules of rituximab and definitions of response (Box 1) make it difficult to collate data from these studies.

Table 5 Efficacy of rituximab in patients with idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritisThe efficacy of rituximab therapy has been assessed in a systematic review of data from 21 studies, including 69 patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy. 117 The complete response rate was 15–20% and the partial response rate was 35–40%. Although these figures are inferior to those reported for treatment with alkylating agents and calcineurin inhibitors, many patients in these studies had previously failed to respond to the above therapies. 117 In a prospective cohort study of 100 consecutive patients with membranous nephropathy who were followed up for 2.5 years after treatment with 1–4 doses of rituximab, complete and partial remission occurred in 27 and 38 patients, respectively, at a median of 7.1 months (range 3.2–12.0 months). 121 One-third of patients in this cohort had failed to respond to previous therapy with other medications. Remission was seen in 47 of 68 (69.1%) patients given rituximab as the primary immunosuppressive agent, and in 18 of 32 (56.3%) patients who received rituximab after the failure of an alternative immunosuppressive agent. Remission rates were similar in a prospective cohort of patients treated with rituximab as first-line therapy and a retrospective cohort of patients who received this agent as second-line therapy and were matched for age, sex and severity of proteinuria. 120 Three separate reports provide information on the efficacy of rituximab in the treatment of patients with post-transplantation recurrence of membranous nephropathy. 117,119,122 Therapy with 1–8 doses of rituximab stabilized renal function and induced complete or partial remission in 13 of 14 patients, 117,119,122 including those who required re-treatment. 122

A prospective study indicates that the proportion of patients with membranous nephropathy who achieve complete and partial remission increases over time, indicating a delayed response. 121 Other studies have also reported increasing rates of remission during extended follow-up 30,114,120 and that remission is sustained after B-cell recovery. These observations might reflect gradual clearance of glomerular immune deposits, correction of pathological abnormalities and/or resolution of proteinuria. Although these patients might relapse, re-treatment with rituximab is effective in inducing further remission. 114,116,118,119,120,121 Most studies do not provide information on the effect of rituximab therapy on kidney function; however, in one study, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increased in patients with complete remission, but progressively declined in those who did not respond to therapy. 121 Other studies confirm that remission of membranous nephropathy improves 30,118 or stabilizes 114,119,120 renal function.

Reports demonstrate that anti-PLA2R antibody titres decline after therapy with rituximab. Antibodies to PLA2R were detected at baseline in 10 of 28 patients treated with rituximab, and were absent in all five patients tested for these antibodies after complete or partial remission. 114 In a case series, a decline in anti-PLA2R antibody titre was associated with a reduction in proteinuria in two patients, whereas the three patients in whom anti-PLA2R antibody titres increased did not enter remission. 115 These findings were confirmed in another study, which showed that patients with decreasing anti-PLA2R antibody levels after rituximab treatment had increased rates of remission at 12 and 24 months. 108

The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines recommend that immunosuppressive therapy should be initiated in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy who have nephrotic syndrome, proteinuria of ≥4 g per day and estimated GFR ≥30 ml/min/1.73 m 2 who fail to respond to 6 months of treatment with antihypertensive and antiproteinuric agents. 107 An initial immunosuppressive regimen that combines corticosteroids and an alkylating agent is recommended, if that fails calcineurin inhibitors should be used. Therapy with 2–4 doses of rituximab is likely to result in complete remission in 20–33% of patients and partial remission in 20–60% of patients who fail to respond to treatment with cyclophosphamide or calcineurin inhibitors. 7 The results of ongoing prospective studies are expected to clarify the benefits of this medication. 125,126

Therapy with rituximab is well tolerated in most patients; however, a number of adverse affects have been documented (Table 6). 4,52,55,62,76,77,127

Table 6 Rituximab-associated adverse effectsAcute reactions can occur within the first 30–120 min of an infusion, 5,117 with an incidence that ranges from 9.1% to 56.3%. 30,47,48,50,51,54,67,79,114,121 Commonly reported reactions include flu-like symptoms, chills, fever, headache, myalgia, itching, erythematous rash, 30,44,47,48,54,55,66,68,117,120,121 cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, tachycardia, 44,48 and hypotension 44,48,121 or hypertension. 44,76 These symptoms can be minimized by pretreatment with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids. The intensity of symptoms declines on stopping the infusion and they rarely recur. Anaphylaxis 54,128 and/or bronchospasm 44,48,65,66,117,121 are rarely reported in association with rituximab infusions. In view of the risk of infusion reactions, cautious administration is advised, beginning with a slow infusion rate and increasing the rate at 30 min intervals. In adult oncology practice, the first dose of rituximab is infused over 6 h and subsequent doses are given over a 4 h period. 129

Patients receiving rituximab are at increased risk of infections with usual or unusual organisms, including pyogenic infections, tuberculosis and cytomegalovirus. 51,117,130 The risk of infections is also increased by concomitant use of other immunosuppressive agents and the underlying disorder. Since CD20 is not present on plasma cells, immunoglobulin production is not altered and the risk of hypogammaglobulinaemia is low (Table 6). 44,47,48,54,61,118,131,132 However, low serum levels of immunoglobulins have been noted in a few patients receiving maintenance rituximab after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, 133 malignancies 134 or autoimmune cytopenias. 135 A meta-analysis of data from three placebo-controlled randomized trials (including 938 patients) of rituximab therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed no increase in the incidence of infections. 136 Systematic reviews of rituximab therapy in patients with lymphomas show that this treatment is associated with a twofold increase in the risk of neutropenia and infections 137,138,139 compared with standard therapy, perhaps as a result of the increased dosage of rituximab and the underlying disease The dose specified is higher than usually used for nephrotic syndrome. Patients with nephrotic syndrome treated with rituximab may show transient leukopenia associated with bacterial sepsis or pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly known as P. carinii), 48,51,52,54,76,140 similar to that reported in patients with haematologic malignancies or rheumatoid arthritis. 141 Therefore, the use of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis should be considered in patients with nephrotic syndrome who are receiving rituximab therapy and concomitant immunosuppression. A report on 19 patients with difficult-to-treat systemic lupus erythematosus who were given two doses of rituximab showed exacerbation of herpes zoster infection in five patients. 142 Another study reported increased infection-related mortality in 77 kidney transplant recipients treated with rituximab. 143 By contrast, infection rates were similar in 170 highly sensitized kidney transplant recipients treated with rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin and in 191 nonsensitized patients who did not receive this combination therapy. 144

Patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and collagen vascular disorders treated with rituximab are at risk of reactivation of hepatitis B infection, resulting in fulminant liver failure. 145 The use of rituximab should, therefore, be avoided in patients who are positive for hepatitis B antigens. 146

Evidence indicates a possible association between long-term rituximab therapy and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an encephalitis caused by JC polyomavirus. 147 Multiple case reports describe PML in rituximab-treated patients with haematological malignancies, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, which have prompted modification of current prescribing information (including a 'black box' warning). 148 Patients with PML show a gradual onset of cognitive impairment, motor weakness, speech problems and deterioration of vision. The diagnosis is made on the basis of these clinical features, MRI findings and demonstration of polyomavirus in brain biopsy samples or cerebrospinal fluid.

PML has not been reported in patients with nephrotic syndrome treated with rituximab. Screening of blood and urine specimens from 11 children with nephrotic syndrome treated with rituximab and eight controls showed the presence of JC virus in the urine of one patient and one control. 149 BK virus was found in the urine of seven patients and two controls, and in blood samples from four patients. 149 The above findings suggest the need for increased awareness regarding these infections in immunocompromised patients.

Rituximab can cause delayed pulmonary toxicity, chiefly in adults treated for B-cell lymphoma 150 and other disorders. 151 Two systematic reviews on rituximab-induced lung disease (in 121 151 and 30 152 patients, respectively) suggest a mortality rate of 14.9–29.0%. Pulmonary symptoms usually occur after a mean of four (range 1–12) doses of rituximab, 1–3 months after the last infusion. Clinical features include dyspnoea, fever, nonproductive cough and hypoxaemia, with bilateral lung infiltrates, reduced diffusion capacity and a restrictive ventilatory pattern. Rarely, patients have hypoxaemia and respiratory insufficiency after the first infusion. 153 Pathological findings include bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, interstitial pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. 154 Acute lung injury with thrombotic microangiopathy, multiorgan dysfunction and death was reported in one patient treated with rituximab for recurrent FSGS. 92

Rituximab should be used cautiously in patients with underlying lung disease, and a diagnosis of rituximab-related lung injury should be considered in any patient who develops respiratory symptoms or new radiographic changes after therapy. Affected patients are treated with supportive care and corticosteroids, although the efficacy of steroids is not proven. 152

Repeated use of rituximab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and lymphoma is associated with the formation of human antichimaeric antibodies. 155,156 The presence of host antibodies to the murine peptide sequences in rituximab might cause an anaphylactic reaction in some patients or, by increasing rituximab clearance, reduce its efficacy. 73,157,158 The presence of human antichimaeric antibodies in six of 14 patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy did not affect the response to rituximab. 30 Development of human antichimaeric antibodies is thought to be linked to the rituximab dosing schedule, since they are more common in patients who received one rather than four doses of this agent. 2,158,159 The development of human antichimaeric antibodies might be minimized with the use of new humanized or fully human monoclonal antibodies against CD20. 160

Rituximab has mild to moderate efficacy and a favourable safety profile in patients with difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome. However, the current literature on its efficacy in this setting is based chiefly on case series and data from very few randomized controlled trials. For this reason, firm recommendations cannot yet be presented for its use in clinical practice. Despite the limitations of the available evidence, satisfactory results have been obtained with rituximab therapy in patients with refractory steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome, recurrent FSGS and membranous nephropathy. By contrast, this treatment has limited benefits in patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Prospective, randomized controlled studies with adequate sample sizes and appropriate follow-up are necessary to define the indications for therapy with rituximab therapy, and to determine outcomes and predictors of response.

We searched PubMed and EMBASE for full-text articles mainly in the English language published from January 2002 to October 2012, using the following terms: “nephrotic syndrome”, “rituximab”, “CD20”, “minimal change”, “focal segmental glomerulosclerosis”, “recurrent FSGS”, “membranous glomerulonephritis” and “membranous nephropathy”. The reference lists of selected publications were reviewed to identify additional relevant articles. To reduce publication bias, we included data from systematic reviews and studies including four or more patients, except in the case of papers relating to recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and adverse effects, for which even single case reports were considered. Studies by the same group of authors were scrutinized to avoid overlap in the reporting of findings derived from the same patients.

The authors would like to acknowledge the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, for supporting their research.